Quick Facts

| Net Worth | Not Known |

| Salary | Not Known |

| Height | Not Known |

| Date of Birth | Not Known |

| Profession | Celebrities |

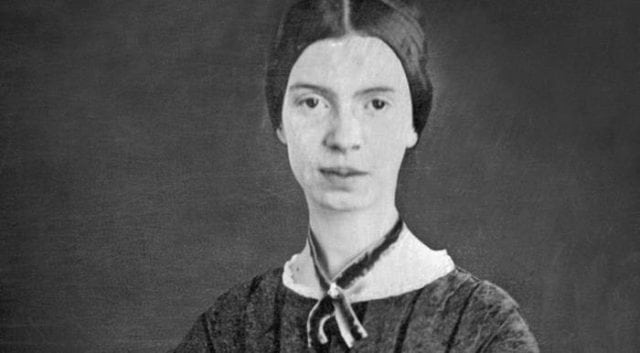

Poetry is when an emotion has found its thoughts and thoughts then find words. This is a great aspect of human life, such that those who have mastery of the art of poetry are termed great. One of such greats is Emily Dickinson, one of the greatest American poets of the 19th century as her works have continued to resonate years after she passed on.

Besides being a great poet, she was also prominent for her unusual lifestyle. Notwithstanding the seclusion and simplicity that ruled her life, she wrote poetry of great power and has been defined as a woman ahead of her time. She is also assumed to be the mother of female writers.

A great number of her poems remained unpublished and were found only after her death while a host of others were published without her knowledge. Her lifetime, though quiet, was infused with such creativity which gave birth to almost 1800 poems, most of which were centered on the themes; death and immortality.

It has been over a century since she transited to the great beyond but her work has continued to hold great relevance and resonate with poets over the years. Moreover, the strength of her literary voice combined with her lifestyle also contributes to the sense of Emily Dickinson as an indelible American personality who continues to be discussed today.

That noted, let’s delve into the life and times of this noble; bio, religion, family, sexuality, and other facts.

Emily Dickinson’s Bio

In the Connecticut River valley situated in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, the United States, a town known as Amherst was posited. On its Main Street stood a mansion built by the patriarch of the Dickinson family and one of the founding fathers of the Amherst College, Samuel Dickinson. The house was known as the Homestead. It was in one of the bedrooms of this mansion, on the 10th day of December 1830, that Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born. The mansion wherein she was born and bred would become her sanctuary for the most part of her life.

When she was 10, she was enrolled alongside her sister at Amherst Academy which was formerly a boys’ school that had opened to female students just two years earlier. Through the seven years she spent in the Academy, Emily took classes in English and classical literature, Latin, botany, geology, history, “mental philosophy,” and arithmetic and was described as a very bright and excellent scholar.

Also, while growing up, she was troubled by the “deepening menace” of death, especially of those close to her, and that became the major theme featured in her poems. During that time also, Emily Dickinson met people who later became lifelong friends and correspondents. They include Abiah Root, Abby Wood, Jane Humphrey, and Susan Huntington Gilbert (her future sister-in-law).

She later moved on to Mary Lyon’s Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (which later became Mount Holyoke College) in South Hadley, about ten miles (16 km) from Amherst where she studied for only 10 months.

Following the death of yet another loved one, her principal and friend, Emily’s high spirits soon turned to melancholy. Consequently, she resorted to confinement and never strayed far from her hometown. She withdrew more from the outside world and social life after her mother became chronically ill and effectively bedridden in the mid-1850s until her death in 1882, as she took it upon herself to remain always with her. Eventually, she successfully secluded herself and was portrayed as an agoraphobic recluse for decades. That period, the 1860s, however, became her most productive writing period although it witnessed a decline in 1866.

She also exhibited other strange behaviours such as talking to visitors from the other side of a door rather than speaking to them face to face and was usually clothed in white whenever she happens to be seen.

After several other deaths in the Homestead, including her father, mother and favourite nephew, Gilbert, who died of typhoid fever, Emily Dickinson’s turn eventually came in 1886. The lady in white succumbed to the cold hands of death on May 15, 1886, at the age of 55 and her cause of death was given as Bright’s disease.

She was buried, laid in a white coffin, in the family plot at West Cemetery on Triangle Street.

Her Writings

Emily Dickinson began writing as a teenager. Her early influences include the principal of Amherst Academy, Humphrey and a family friend named Benjamin Franklin Newton, who sent her a book of poetry by Ralph Waldo Emerson as well as introduced her to the writings of William Wordsworth. He was a formative influence on the young poet and believed in her, recognized her exceptional mind as well as encouraged her talent. He died of tuberculosis and Emily long paid tribute to him.

Her writings were also influenced by the Bible as well as contemporary popular literature such as Lydia Maria Child’s Letters from New York, (another gift from Newton), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Kavanagh, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre as well as by the great writer, William Shakespeare. Also, she established great friendships that helped to develop and expand her art.

Her friendship with her sister-in-law, Susan developed in the 1850s and helped expand her horizon. Moreover, their sharing of books and ideas was a vital component of Emily’s intellectual life. In her later days, Emily wrote to Susan, “With the exception of Shakespeare, you have told me of more knowledge than anyone living. To say that sincerely is strange praise”.

In 1855, she ventured outside of Amherst, as far as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where she befriended a minister named Charles Wadsworth. He would also become a cherished correspondent until his death in 1882. Emily also kept so many other correspondents until her death and requested her sister to burn her papers.

In the summer of 1858, she reviewed poems she had written previously and begun making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books. She, in turn, created forty fascicles which held nearly eight hundred poems from then through 1865, though no one knew of these books until after her death.

Her first collection of poetry was published in 1890 by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd, though both heavily edited the content. However, scholar Thomas H. Johnson later published another of her poetry collections titled The Poems of Emily Dickinson in 1995. Johnson’s version became the first complete and mostly unaltered version of Emily’s work ever released. At her death, she left behind phenomenal works of art.

Religion

Emily was raised in a Calvinist household and attended services with her family at Amherst’s First Congregational Church. As a teenager, she confessed her faith in Christ alongside her friends in 1845, during a religious revival. Following the experience, she described the feeling of finding her saviour like a perfect peace and happiness in a letter she wrote to her friend a year later. Moreover, communing alone with the great God and knowing that he would listen to her prayers was the greatest pleasure therein. Besides, the formal declaration of faith was necessary to become a full member of the church.

The experience for her was, however, not meant to last a lifetime. In order to remain true to herself rather than out of defiance, she attended services regularly for only a few years. Despite her rejection of the orthodox religion, Emily addressed matters of faith in her poetry. One of them written circa 1852 has an opening which read “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – I keep it, staying at home” implying that her attitude toward spiritual matters was more complex than her poem.

Additionally, her tone varies greatly. While some affirm the need for faith, others were based on irreverence and some at times expresses outright anger with an absent God. Despite her seeming rebellion against faith and her decision to keep the Sabbath staying at home, she maintained a sound spiritual health as assessed by Rev. Jonathan Jenkins, minister of First Church from 1867-77 as per her father’s request. Ultimately, she never joined a particular church or denomination, steadfastly going against the religious norms of the time although the events in her life such as the death of loved ones, the Civil War, and close observation of nature’s cycles, prompted poetic musings on religious themes throughout her life.

Emily Dickinson’s Family

Dickinson family was a very prominent one. Though she was known as a recluse in the later part of her life, her whole life revolved around her family with whom she built and maintained a strong relationship. They lived either with or near one another their entire lives. Family for her meant her parents and siblings.

The poet’s parents were Edward Dickinson (1803-1874), a lawyer and the eldest of Samuel Dickinson’s nine children, and Emily Norcross of Monson, Massachusetts (1804-1882), also the eldest of nine children. The duo got married on May 6, 1828, after two and a half years of courting and had three children together. Emily’s father also served as a trustee of Amherst College as well as its treasurer for almost four decades. Moreover, he was at the forefront of the town’s leadership and led a disciplined, civic-minded public life. His services include representing Amherst in the state legislature for several terms as well as representing the Hampshire district in the United State Congress.

Emily was the younger sister of William Austin (1829-1895) aka Austin, Aust or Awe and the elder sister of Lavinia Norcross (1833-1899) who the poet was extremely close with. Her sister Lavinia was also known as Lavinia or Vinnie and it was she who led the crusade to publish her sister’s poems. Like her sister, Vinnie also died unwed.

Austin married Susan (1830-1913), Emily’s close friend and correspondent in 1856. The couple lived in a house close to the Homestead, the Evergreens, which was built by their father, Edward Dickinson. They had three children including Edward Austin (1861-1898), Martha (1866-1943) who published the later part of her aunt’s work, and Thomas (1875-1883).

Was She a Lesbian?

Dickinson never married but had a number of relationships during her life time. Most of her friendships, however, depended entirely upon correspondence. One of the most outstanding is the one she had with her sister-in-law Susan who she shared a strong and affectionate relationship with. Susan critiqued her poems, prompting her to work harder than ever. She received over 300 letters from the poet, more than any other correspondent, and being a writer herself, she wrote Emily’s striking obituary, which appeared in the Springfield Republican on May 18, 1886. Their intimate correspondence also contributed to the speculations about the poet’s sexuality. It has been argued that she may have been lesbian or at most bisexual.

Although there is little evidence on which to base a conclusion about the objects of her affection, her understanding of passion can be inferred through some of her poems and letters. While different theories abound about her, one thing remains that she certainly valued her friends. Another is that her poetry was heavily edited by several people before being released into the public posthumously thus, making it almost impossible to discern whether she had romantic feelings for women or not.

Other Facts About Emily Dickinson

1. Their homestead is now a museum dedicated to her.

2. Fewer than a dozen of her poems were published during her lifetime as she kept most of her works to herself.

3. She had a passion for Botany in her early years and with her sister, tended the garden in their homestead.

4. Her major themes include morbidity, master, nature and she frequently used humour, puns, irony and satire in her poetry.

Top 3 Richest Celebrities

Also Read: Top 10 Richest People in the world with full biography and details.